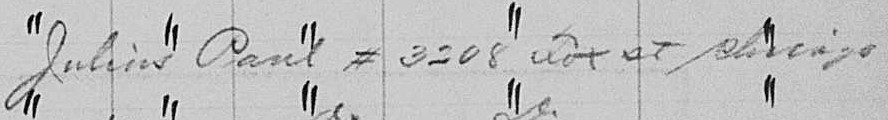

As soon as Brunis, Helen, and their relative Bertha Henkelmann disembarked from the Markomannia in Philadelphia on 13 July 1895, they made their way by train to Julius in Chicago. The ship manifest even lists Julius’s address in Chicago: 3208 Fox Street.

Perhaps Julius’s letters home had prepared Brunis for what she was about to encounter. But no letter could have truly softened the shock of moving between a small rural village in Poland and the urban hive in which Julius had settled.

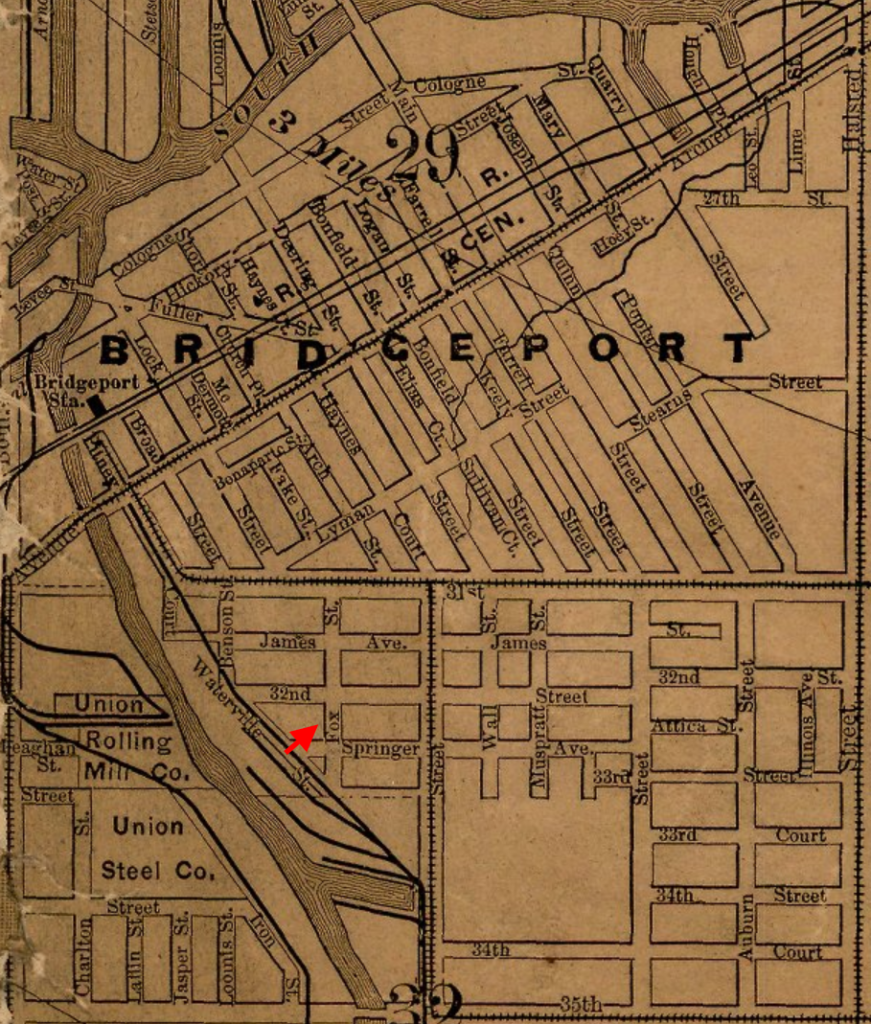

Fox Street is the current-day South Throop Street, located in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood. Bridgeport is nestled up against a curve in the South Branch of the Chicago River forming both its northern and western border. In 1895 the din, smoke, and stench of the neighborhood must have been incredible. The Paul family lived just two blocks east of the river. All the land between them and the river was occupied by a steam train railroad yard. On the other side of the river belched and fumed two great steel mills: the Union Rolling Mill plant producing steel rails; and the Union Steel plant producing steel billets. Streetcar lines ran down 31st Street two blocks to the north and Ullmann Street (now S. Racine Avenue) one block to the east. The noise and air pollution from all this activity were surely tremendous.

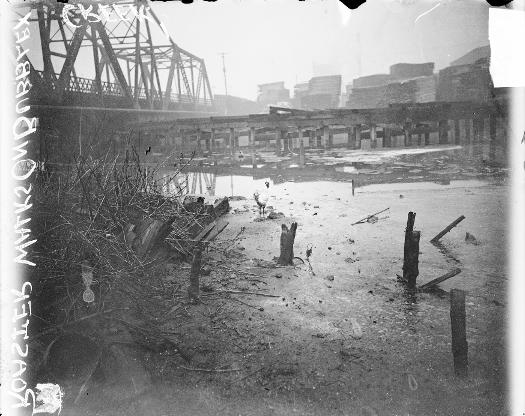

But that was surely nothing compared to the river itself. The south fork of the South Branch of the Chicago River bordering Bridgeport on the west had, according to one area resident, “many local names … most unprintable. The one that stuck was Bubbly Creek.” At its terminus not quite a mile south of the Paul home stood the vast and world-famous Union Stock Yards. Its complex of livestock pens, packing houses, canning factories, fertilizer plants, glue works and railyards covered over 600 acres of land and made Chicago the “hog butcher for the world”. They also gave Bubbly Creek its name. Hundreds of thousands of gallons of river water were pumped into and out of the stockyards every day. As the water was returned to the river, it became saturated with animal waste, blood, and entrails. As the offal sank to the bottom and decomposed, bubbles of methane and hydrogen sulfide gas rose continually from the river bed to the surface, releasing a characteristic rotten egg smell.

This is how Upton Sinclair described Bubbly Creek in his famous 1906 novel The Jungle :

’Bubbly Creek’ is an arm of the Chicago River, and forms the southern boundary of the yards: all the drainage of the square mile of packing houses empties into it, so that it is really a great open sewer a hundred or two feet wide. One long arm of it is blind, and the filth stays there forever and a day. The grease and chemicals that are poured into it undergo all sorts of strange transformations, which are the cause of its name; it is constantly in motion, as if huge fish were feeding in it, or great leviathans disporting themselves in its depths. Bubbles of carbonic acid gas will rise to the surface and burst, and make rings two or three feet wide. Here and there the grease and filth have caked solid, and the creek looks like a bed of lava; chickens walk about on it, feeding, and many times an unwary stranger has started to stroll across, and vanished temporarily. The packers used to leave the creek that way, till every now and then the surface would catch on fire and burn furiously, and the fire department would have to come and put it out. Once, however, an ingenious stranger came and started to gather this filth in scows, to make lard out of; then the packers took the cue, and got out an injunction to stop him, and afterward gathered it themselves. The banks of ‘Bubbly Creek’ are plastered thick with hairs, and this also the packers gather and clean.

Imagine what a shock this must have been to our ancestors! One day they are living in a tiny German farming village in Poland with a population under 100 people. The next they find themselves in a great metropolis of well over a million residents living beside a toxic industrial waste site. One can imagine that Brunis in particular wondered more than once over what she had gotten herself into.

SOURCES

Libby Hill, The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History (2016).

University of Chicago Library, “Chicago in the 1890s“.

Chicago Sun-Times, “Plagued by waste and organic rot, Bubbly Creek heads for restoration“. [CLICK THIS LINK TO WATCH THE CONTEMPORARY BUBBLY CREEK ACTUALLY BUBBLE!]