The tremendous haphazard industrial growth of Chicago in the late nineteenth century gave rise to two neighborhoods at the nadir of the city’s material poverty: the Stockyards and South Chicago. Our Paul ancestors lived in both.

Sanitation was a constant concern and a constant challenge in working class Chicago, as it was in every rapidly expanding industrial city of the age. In 1901 the City Homes Association, a local Chicago housing reform organization including the famous and indominable Jane Addams, published a report on tenement housing in the city with an eye toward legal and material reform. The report was so influential that it led to the 1902 Tenement House Ordinance in the city covering all housing of two or more apartments. Unfortunately the Pauls didn’t stay in Chicago long enough to enjoy the benefits of the new law, but the report did lend tremendous insight into what live was like for our ancestors living in the poorest section of the city over a century ago.

According to that 1901 report, “the conditions of the Stock Yards district and of South Chicago … show the most abominable outside sanitary conditions”. Going even further, the report notes that “the worst district in South Chicago lies between Eighty-third and Eighty-seventh streets and between Ontario and Green Bay Avenue”. In other words, the most unhealthy section of the most unhealthy district in Chicago at the turn of the twentieth century was the Bush! Here is a glimpse of our ancestors’ neighborhood:

The entire district lies in a swamp, and the houses are built upon land which is about eight feet below the city datum.[1] In some places the sidewalks are eight feet above the lots and the street. There is no sewerage unless that name is given to a system of gutters by which a certain amount of sewage is carried off. There is usually an odor from the foul waste matter which accumulates in these places. The land is undrained and in some cases the water stands for months under the houses and upon vacant lots. In certain places there was a green scum upon the water which showed that it had been standing stagnant for some time. There are no water-closets and the outlawed privy vault is in general use. The yards, streets, and alleys are indiscriminately used for the disposal of all sorts of garbage and rubbish. Almost no garbage boxes were found. None of the streets are paved, and the whole district is filthy beyond description. The atmosphere of the neighborhood is clouded with smoke and the district is extremely dreary, ugly, and unhealthful.

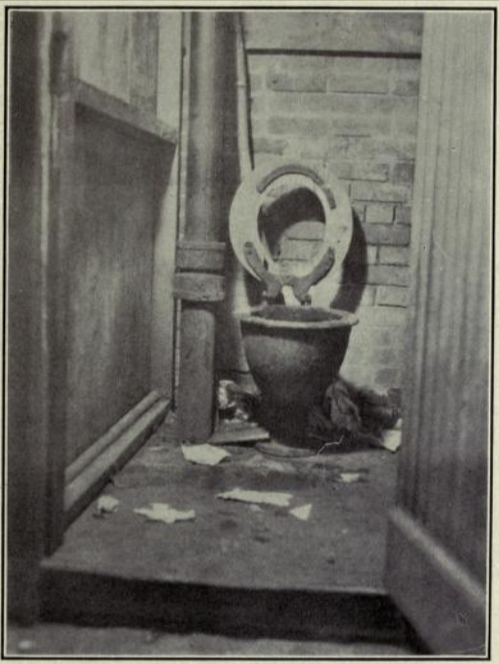

The ‘privy vault’ and the related ‘yard closet’ were an especially horrible feature of life in South Chicago. The privy vault was a shed located generally on the back part of one of the long Chicago city lots. Inside was a hole in the ground with a seat built atop it. Some had no connection to the sewer at all, essentially a traditional outhouse. Others had a connection, but the connection was open and untrapped. There was no mechanical flushing; disposal of accumulated waste had to be manually flushed by users with either collected rainwater or a hose from a nearly public hydrant. The yard closet was a more developed version of the privy vault, connected to the public sewer and enjoying both a trap and a mechanical flushing system, yet also located in a shed outside the apartment requiring a long walk to access it.[2]

Cleanliness and privacy were difficult or even impossible to achieve in such circumstances. In general a single outdoor privy or closet was shared by at least two and sometimes more of the families living in a single building. As late as 1911, nine years after the yard closet was banned and seventeen years after the privy vault was outlawed, 57% of the residents of the Bush were still using these kinds of toilets, and 30% of all toilets, including those inside buildings, were regularly utilized by eleven or more persons from multiple families.

Considering such sanitary conditions, it is unsurprising that infectious disease was prevalent in the Bush, especially among the neighborhood’s children. Diarrheal diseases were particularly common and they took the lives of the first two Paul children born in America.

On 26 April 1896, less than ten months after arriving in Chicago, Brunis gave birth to her second child and first son, Richard. Brunis had a younger brother named Richard; perhaps she and Julius named the boy after his uncle in Poland. We don’t know how healthy the baby was at birth, but records tell us that he fell ill on 6 May. Twenty-four hours later little Richard was dead. His cause of death is listed as “inflammation of bowels”, what we would probably today call gastroenteritis. Beset by abdominal cramps, fever, and diarrhea, even today hundreds of thousands of infants in developing countries still die from it every year. Julius and Brunis buried their son on 9 May in Oak Woods Cemetery on the city’s south side.

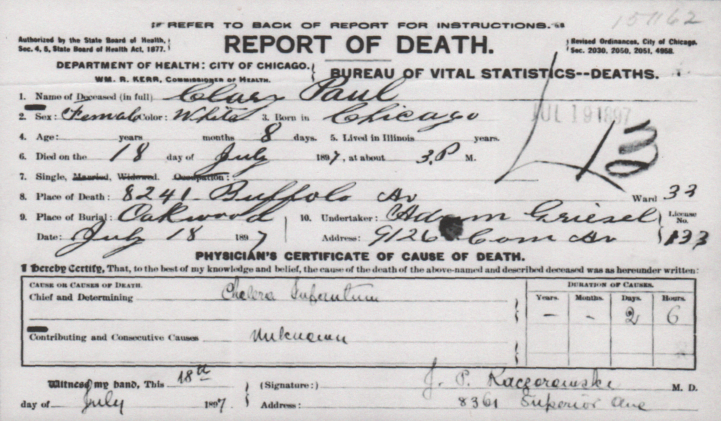

The next year Brunis gave birth to her third child and second daughter. Clara Paul was born 10 July 1897 and her parents called her Clary. At only six days old, the baby fell ill with severe diarrhea. Vomiting and a spiking fever followed, possibly as high as 106 degrees. She eventually became emaciated and listless, her breathing irregular. After battling for two days and six hours, little Clary succumbed. The cause of death on her city death record is “cholera infantum,” an intestinal inflammation with cholera-like symptoms caused by a bacterial infection from contaminated water. This “summer diarrhea” was once a leading cause of death among American infants living in crowded urban conditions during hot and humid summer weather. For the second time in only fourteen months, Julius and Brunis buried an infant in Oak Woods Cemetery.

[1] The Chicago city datum is defined as an elevation roughly 20 feet above the level of Lake Michigan.

[2] The privy vault had been illegal in Chicago since 1894. The yard closet was banned in 1902.

SOURCES

Robert Hunter, Tenement Conditions in Chicago (1901)

Sophonisba P. Breckinridge and Edith Abbott, “Chicago housing conditions, V: South Chicago at the gates of the steel mills,” American Journal of Sociology 17 (2) (September 1911).

Udetta D. Brown, A Brief Survey of Housing Conditions in Bridgeport, Connecticut (1914).