It didn’t take long for the Pauls to put Bubbly Creek behind them. The next year after Brunis and Helen’s arrival, the family moved from the Bridgeport neighborhood to a part of South Chicago known as ‘the Bush’. They spent the next seven years there which amounted to the rest of their time in Chicago.

Before the area’s industrialization in the 1870s, the Bush was a sandy expanse of Lake Michigan shoreline covered in thick wild bushes which gave it its name. In our ancestors’ day, however, there was nary a bush to be found and south of 87th Street the shore couldn’t even be seen. Neither the sidewalks nor the streets were paved. The land drained poorly if at all. Standing water persisted in vacant lots for months at a time. Smoke and soot clouded and covered everything. The family’s move from Bubbly Creek wasn’t much of an improvement at all. In the view of a 1911 research project conducted by Russell Sage Foundation research students and scholars associated with the newly established Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy (later integrated into the University of Chicago), no part of Chicago “more closely resemble[d] the stockyards district” than did the Bush.

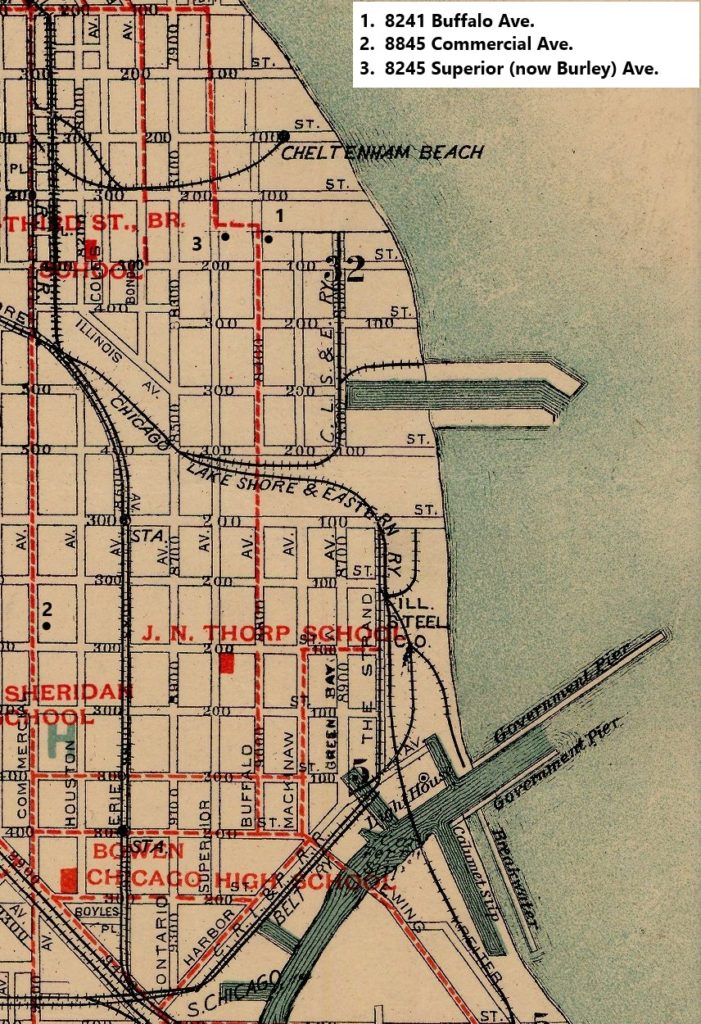

We know from Chicago city directories that the Pauls lived at three different addresses in the Bush:

- 8241 Buffalo Avenue (1896-97 & 1901-02)

- 8845 Commercial Avenue (1898)

- 8245 Superior (now Burley) Avenue (1899-1900)

The two buildings on Buffalo and Superior were located only a block apart. At the time an electric trolley line ran up straight up Buffalo Avenue and turned westwards just in front of their house. The long-gone Cheltenham Beach railway station lay just two blocks away. The massive Polish church St. Michael the Archangel on South Shore Drive (then Bond Street) and 83rd Street which dominates the local skyline today was yet to be built.

South Chicago’s immigrant working-class housing was quite unlike the famous depictions of New York City tenements we are all probably familiar with. The six- or seven-story walk up apartment building crammed onto a tiny lot was unfamiliar in sprawling Chicago. Instead housing outside the center city was dominated by small wood frame structures. In the Bush, the characteristic structure was a wood frame building of one or two stories. The 1911 report mentioned above described the neighborhood’s housing stock as a “dreary succession of small frame dwellings, dull in color, frequently dilapidated, uninviting, and monotonous.” Some were single-family houses, while the largest were two- (or rarely three)-story buildings divided into four apartments. Many of these were former one-story single-family houses added on to over time by the owners to increase the number of renters that could be accommodated. 8845 Commercial was a building of two apartments while both 8241 Buffalo and 8245 Superior had four units each. Unfortunately we don’t know how large any of these buildings or apartments were, but we can be sure they were small. The four-room apartment was typical for the neighborhood. Lots were narrow, just 25 feet facing the street, and such zoning made for long narrow buildings separated by dark narrow alleyways. Unsurprisingly many rooms suffered from poor ventilation and lighting, and overcrowding was common.

At the same time these lots were very long, 140 feet in the Bush, making for large back yards that might join together in the center of the block. Sometimes small ‘back houses’ were built on these sections. As most of the residents were European peasants only recently removed from rural life, locals routinely kept small farm animals in these back lots in constructed yard sheds. They might even keep them under their home if it was raised up on pillars. During the winter months animals were often kept in attics, basements, or even in rooms of apartments. While chickens, ducks, and geese were the most common livestock, even goats and pigs could be found living in the Bush.

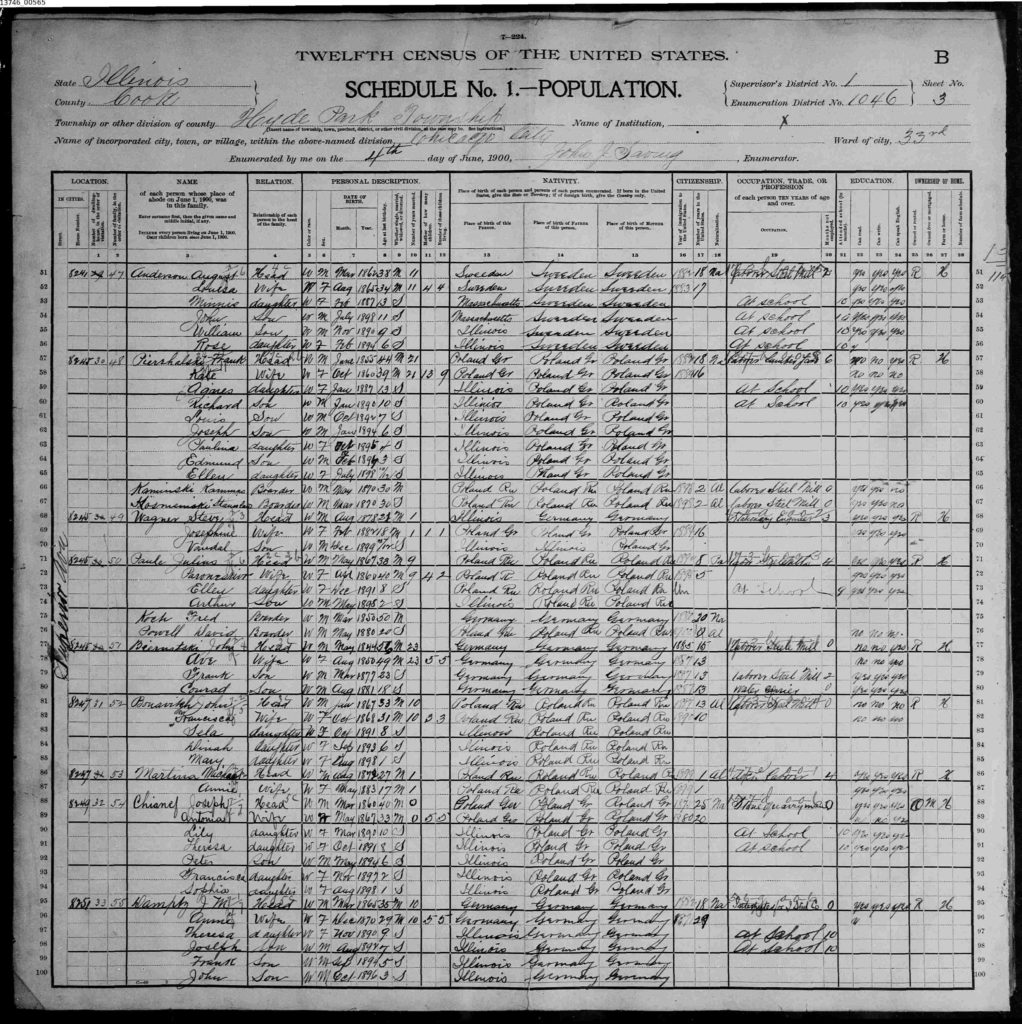

Like many residents of the area, Julius and Brunis took in lodgers, either to help pay the rent, as a favor to friends or relatives from the old country, or both. According to the 1900 US Census, the little family of four (Arthur had been born by this time) hosted two boarders: fifty-year-old Fred Koch from Germany, a married man who had been in America twenty years; and twenty-year old David Powell from Poland who had just arrived in the country. In the years the Pauls lived here, this part of Chicago was heavily Polish. Even though Julius and Brunis were Germans, they probably spoke at least passing Polish as well and perhaps even recalled a little of the old country in the Bush.

SOURCES

Sophonisba P. Breckinridge and Edith Abbott, “Chicago housing conditions, V: South Chicago at the gates of the steel mills,” American Journal of Sociology 17 (2) (September 1911), 145-176.

Map Collection, University of Chicago Library.

“The importance of streetcars,” Industrial History.

A portion of an 1897 Rufus Blanchard map of Chicago showing the addresses of the Pauls in the Bush between 1896 & 1902. The red dashed lines represent electric trolley lines.

A portion of an 1897 Rufus Blanchard map of Chicago showing the addresses of the Pauls in the Bush between 1896 & 1902. The red dashed lines represent electric trolley lines.

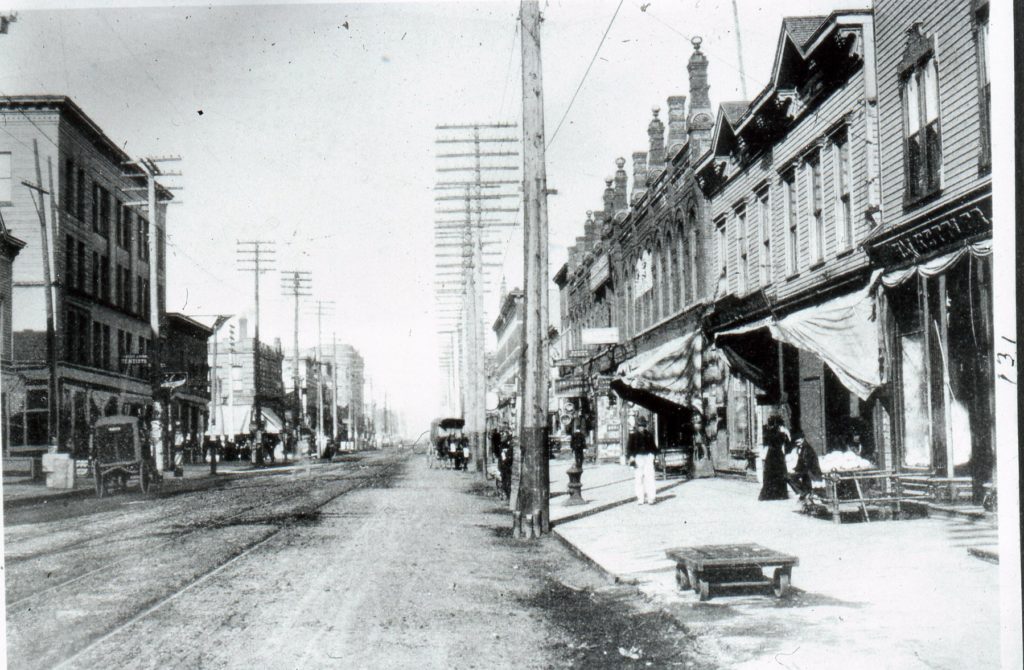

A scene of Commercial Avenue, Chicago, at 93rd Street looking north (c1905).

A scene of Commercial Avenue, Chicago, at 93rd Street looking north (c1905).

A page of the 1900 US Census showing the Julius & Brunis Paul family living at 8245 Superior (now Burley) Avenue.

A page of the 1900 US Census showing the Julius & Brunis Paul family living at 8245 Superior (now Burley) Avenue.