Disembarking in West Hartlepool was the beginning of nearly a week in England for Julius Paul and the Krügers. As West Hartlepool had few lodging houses and little to recommend it, their first order of business was boarding a train for England’s west coast. While migrants transiting England landed in many North Sea ports, the vast majority of them were ultimately headed for one place: Liverpool. This great port city, Britain’s second largest port after London, was the center of the country’s migrant trade. UK flag ships carried not only European transmigrants but emigrants from Britain and Ireland as well.

After arriving in Liverpool, Julius most likely stayed in a hotel. Each of the great British shipping lines operated its own hotel system in the city for its passengers during their wait for their steamer across the ocean. In fact, the entire complicated set of lodging houses and connections — Ruhleben to Hamburg to West Hartlepool to Liverpool to New York, each leg on a different transport — was probably put together by a travel agency in Europe and reflected in a “through-ticket” held by the migrant from beginning to end.

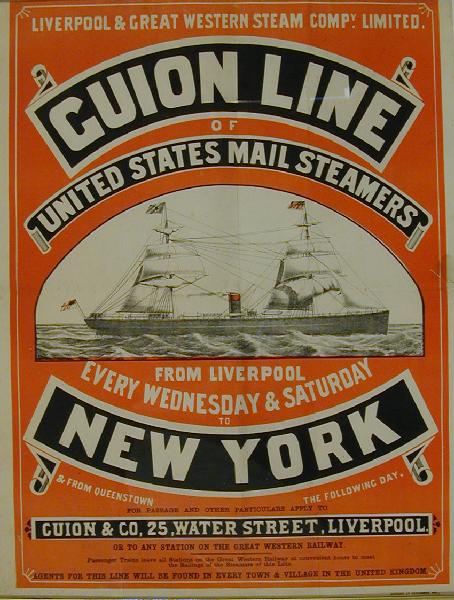

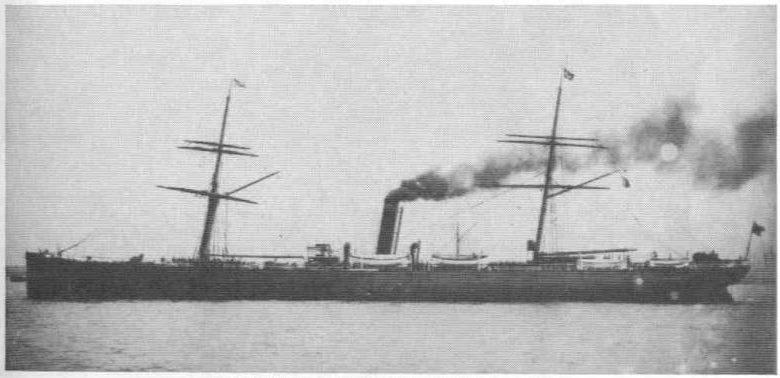

Julius’s ticket for the ultimate leg of his journey was for travel on the ship SS Wisconsin operated by the Liverpool and Great Western Steamship Company, commonly known as the Guion Line. The Wisconsin was an aged vessel, built in the shipyards of Jarrow, England in 1870 and scrapped the year after Julius’s voyage. It was 378 feet long and 3700 GRT, with three decks, two sailing masts, and one funnel to release the smoke from the ship’s single screw engine (in Britain, SS stood for “single-screw steamship”). The Wisconsin could transport 976 passengers per voyage: 76 in first class, 100 in second class, and 800 in third class, aka steerage or ‘tweendeck. It also doubled as a mail steamer transporting letters and packages across the Atlantic.

On the morning of 7 May 1892, a horse-drawn wagonette collected Julius and the Krügers along with their baggage — one piece each — and transported them to the Alexandra dock where they boarded the Wisconsin. Julius and his relatives of course sailed steerage. I assume we’ve all seen the movie “Titanic” with its spartan but clean and cozy quarters with lots of jolly entertainment from the peasant and working class travelers. I doubt things were quite so pleasant for Julius and his companions. Steerage at this time generally meant being packed together in cramped underdeck quarters, open berth accommodations sleeping 100 or more to a room, few toilets, crying children, rare ventures up on deck to enjoy some fresh air. The Wisconsin’s passenger list shows people from all across northern Europe: Ireland, England, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Germany, Poland, Russia, even a few from Italy, France, and the United States. Fourteen Mormon missionaries were on board heading back to Utah, as well as a 32-year-old stowaway named J. Cook. 695 ticketed passengers boarded in Liverpool. The ship made one stop, in Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland near Cork, and picked up another 184 before heading out into the Atlantic.

Twelve days later, on 19 May 1892, Julius sailed into New York Harbor under the shadow of the Statue of Liberty. It was his twenty-fifth birthday. He disembarked onto a barge or ferry boat which transported all of the Wisconsin’s steerage passengers to the brand new immigration control station on Ellis Island. The facility had opened only five months earlier (unfortunately the original station Julius passed through was destroyed by fire in 1897), an impressive collection of buildings constructed of Georgia pine. After walking down a long wooden boardwalk to the main inspection building, would-be immigrants met with medical inspectors and the immigration registrars. After passing inspection, Julius and the Krügers passed into a wide hall in which all manner of welcome awaited. Perhaps they bought a light meal here, were greeted by representatives of a local German Lutheran congregation, changed money, or bought a train ticket. At the end they boarded another small barge, their final ship, that took them into New York City. Their new lives had begun.

[The Wisconsin’s passenger manifest entries for Julius and the Krügers. It mistakenly records their country of citizenship as “Germany,” most likely either because they were ethnic Germans or because they began their journey in Hamburg. “Yes” indicates an ability to read and write. The figures in the final column are the number of pieces of baggage for each passenger. Julius had one while the Krügers shared three between them.]

SOURCES

Nicholas J. Evans, Aliens en route: European transmigration through Britain, 1836-1914. PhD dissertation, University of Hull, 2006.

Drew Keeling, “Oceanic travel conditions and American immigration, 1890-1914,” Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper No. 47850, 26 June 2013.

“Ellis Island Immigration Experience,” GG Archives.

Peabody Essex Museum.

Merseyside Maritime Museum.

The Graphic, 28 November 1891 issue.